What if your notes could talk to each other – and help you think better?

That’s the magic of Zettelkasten system developed by German sociologist Niklas Luhmann (“zettel-kasten” = “paperslip-box” in German). It’s not about storing information – it’s about creating a network of ideas, all connected, all growing together. With a simple structure and a clever use of links, this method turns your notes into something more powerful: a second brain!

My interpretation and implementation of this system:

BikeGremlin Deathnotes – My Zettelkasten System

0. Introduction

I suggest you read this whole article in one go, quickly, just to see what’s there – and get confused. That’s good, that’s normal. If you haven’t used a system like this before, don’t try to understand it on the first go. 🙂

Only on the second read try to take it section by section and understand where each one fits in the whole picture.

After that, if you like the idea, you can read about the Obsidian: a free tool that can help you with this system!

1. The Basic Structure

Niklas Luhmann is the founder of Zettelkasten system. He needed a way to connect ideas, while being able to quickly find what you need, but without having rigid, separate, structured categories.

So, he came up with numbered notes or paperslips (“zettel” in german) and a linking list on each note. Every paperslip/note has a fixed address.

Source: zettelkasten.de

Zettelkasten scales better than the “normal” notes thanks to (not despite) having a more organic structure – as opposed to a rigid hierarchy tree.

Luhmann didn’t use tags to organize his notes! Just central pages for a topic, as entry points, and then you just follow links (like Wikipedia – and BikeGremlin websites 🙂 ).

Source: zettelkasten.de

1.1. Paperslip Structure

Each paperslip (or “note” if you like) has:

- Unique identifier.

- Body / Content.

- Footer / references.

1.2. Zettelkasten vs Zettel (System vs Parts)

To reiterate: the system of connected notes is called “Zettelkasten” (eng. “notebox“), and each note is called Zettel (eng. paperslip).

Let’s move on to the more exciting part(s). 🙂

2. Death-notes 😈 – Zettel – “Atomic Notes”

Some authors refer to these “zettel” notes as “atomic notes” for being very short (the notes, not the authors 🙂 ). In my native, that would be “papirić” (small piece of paper), but as I’m writing this in English and since I’m a manga and anime fan, I’ll call this chapter “death-notes.” 🙂

The main building block of our second brain system are the death-notes. Here is how each of them should be made for the system to be effective:

- Interlinked (hyper-textual).

- Atomic (one idea – one note).

- Personal (subjective)!

Let’s discuss these three “ingredients” in reversed order:

2.3. Personal

For the system to work for you, it is crucial to write in your own words!

That forces you to think and memorize better, and notice any gaps in your knowledge (long article about the benefits of writing). You get none of these benefits if you just copy/paste stuff in your notes.

For example: I’m using the term “death-notes”. It helps me memorize the basic idea (as explained in this article) through association and analogies in my brain (the way my brain works). This helps me learn and remember.

2.2. Atomic

For the notes to work, they should be short. Keep one idea per note. If you have more ideas, link to other notes.

For example: A note that talks about when to replace a bicycle chain: “Bicycle chain should be replaced when elongated by more than 0.5%.” I could write a bit more about what happens when you don’t replace the chain on time, but that’s it, at least for that note.

2.1. Interlinked

Notes should be linked, but that’s not all. The reason for linking should be explicit (explained in the note). Without that information, you are not creating your own knowledge (for your future self). Context matters.

So, I can’t just say “link” or “link-to-note-9584“, but something that lets your future self know what the linked note is about, like: “Heterarchy explained – wiki” (OK, in this case I’m linking to a full article, but you get the idea).

For example: The above-mentioned note about when to replace a bicycle chain. I know that clean and lubricated chain lasts longer (wears slower). A note explaining that should be linked to from the chain-wear note. Likewise, the chain-lubrication note should link to the chain-wear note.

3. Hierarchy, Structure?

Now, you may wonder:

“If I put many ideas into lots of short (death)notes, even if they’re interlinked, won’t it just be one big mess?“

Worry not, my friend, there is a method to the chaos.

Notes are still structured, at least in a way (despite their organic non-linear linking). It is just not a one-way strict hierarchy (it’s more of a “heterarchy”).

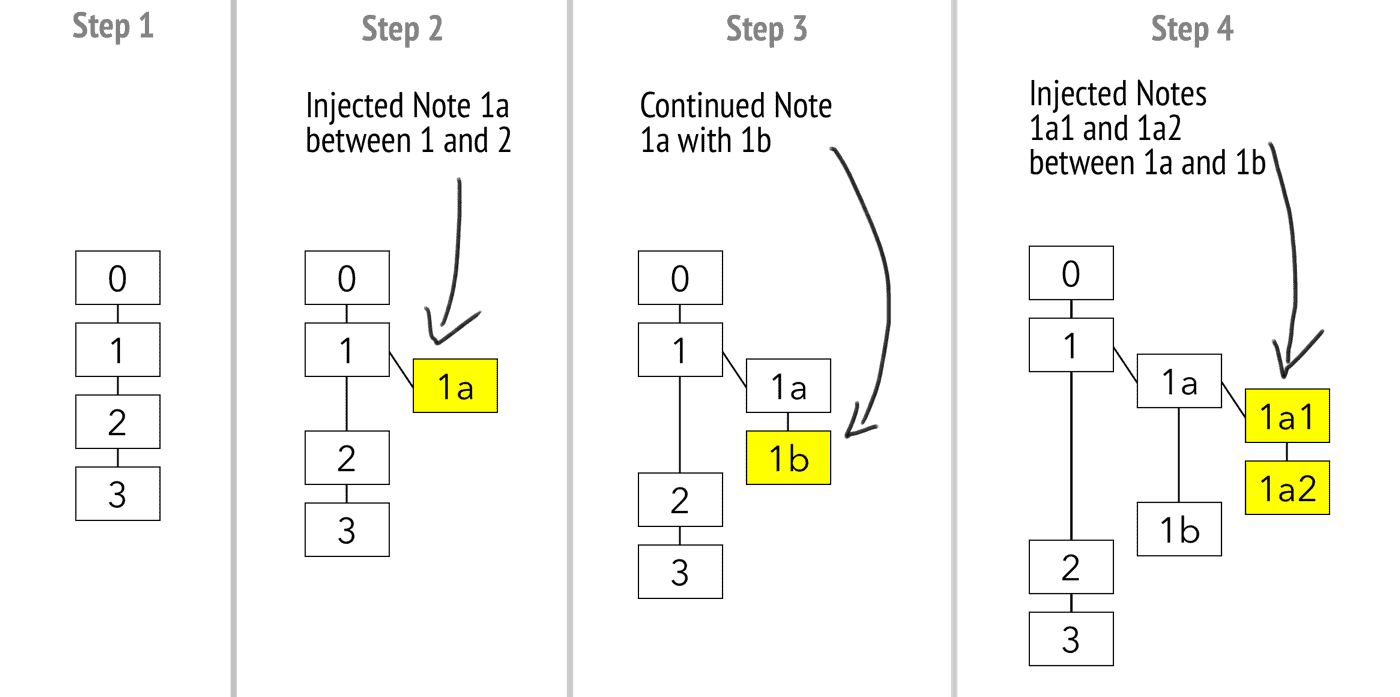

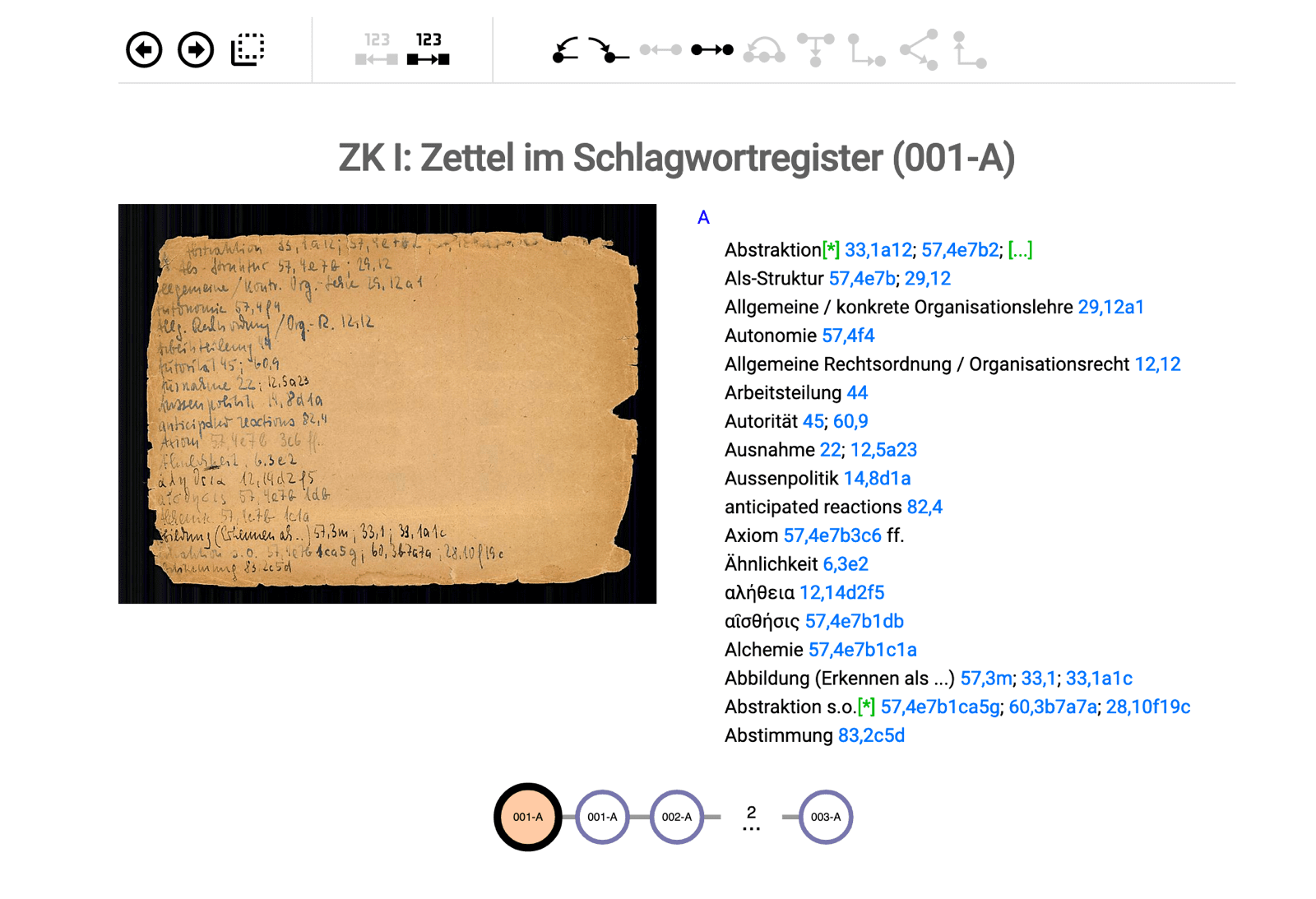

Zettelkasten’s inventor, Luhmann, used a register with a link to only most relevant notes for each term. The next three pictures speak clearer than words – a text list, a graph showing the text list’s logic, and a graph of the “heterarchy”-like structure:

Source: zettelkasten.de

Source: zettelkasten.de

An interesting caveat is that one note can have several notes referring to it:

Source: zettelkasten.de

This system resembles a good football team. It is more fluid than rigid.

We can build an attack:

Goalkeeper -> Defender -> Midfielder -> Striker

But we can also do “unexpected plays:”

Goalkeeper -> Striker

(long throw that will initiate a counter-attack when reasonable)

As well as “long balls:”

Defender -> Striker

(again, similar as the example above)

As you can see: if it is all reasonably organized and connected, it gives more power, without adding (a lot) more chaos!

| Football Concept | Zettelkasten Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Fluid formation | Notes don’t belong to just one category |

| Context-driven play | Meaning emerges from where a note is linked |

| Long balls / short passes | Direct or gradual reasoning paths |

| Tactical flexibility | Structure notes adapt to current line of thought |

| Coordinated strategy | Strong linking + thoughtful note writing |

Table 1

Like a good team:

It’s not chaos, it’s orchestrated flexibility.

The more you train it (write and link intentionally), the more powerfully it plays.

My Obsidian use of “tags” and “indexes” works in this way:

- Tags are like playmakers.

They connect related notes fluidly, without the rigidity of folders. They organise by meaning, not by location. - Indexes are like tactical overviews.

They show bigger-picture flows, strategies, and sequences – guiding you through related concepts or note clusters like a coach’s match plan. - Notes are like players.

Depending on context, each note can play different roles – sometimes a defender (background info), sometimes a striker (main idea), or a midfielder (connector, sources and references). The hyperlinks define the formation.

13. Instead of a foreword

War… war never changes.

Wait, no – that’s for a different article!

Now, where was I? Ah, yes:

Google is broken. It sucks – and has sucked since before the start of 2024 (with a tendency of getting worse). For months now I’ve been looking for a good alternative, because Google no longer keeps my writing and articles in its index, or at least won’t show them when I search for them, e.g. using the search limiter “site:bike.bikegremlin.com the-term-I-know-I-wrote-about” (it gives nothing – and when I search without the limiter, I just get random Reddit posts LOL).

I was looking for an alternative, for months. Haven’t got the money or resources to make and host my own search engine, and solutions that can be simple enough to self-host while being cheap enough are hard to find. That’s when I came across Obsidian (first) and Zettelkasten (right after that). Relatively recently before writing this article.

Long before I knew the term Zettelkasten, I had already been connecting ideas across notes, linking concepts through logic (and BikeGremlin site articles) rather than folders, and writing things in my own words to truly understand them. When I finally came across this “named system,” it didn’t feel like a revelation: it felt more like finding a name for something I’d already been doing.

This system fits how my brain works: I think in webs, not trees. One idea leads to another: sometimes through logical paths, sometimes with crazy detours or sudden jumps/shortcuts. So, I need flexibility, but not chaos. That’s why this method works so well for me – and why I’m writing this article. Not to sell you a system, but to share something that made thinking, writing, and learning feel more natural (to me).

Just like in a bike workshop (or on a football pitch), everything has its place – but the real magic happens when you combine things creatively, when the parts work together fluidly. Zettelkasten isn’t about rigid control. It’s about orchestrated flexibility. For someone like me – who likes systems that grow, evolve, and stay out of the way – that’s the perfect match.

42. Sources

- zettelkasten.de

A great resource for anything Zettelkasten-related, with great introductory & tutorial articles, and a forum. - Obsidian.md Installation and Configuration

My article that explains how to install and configure Obsidian.md software to use as a digital Zettelkasten tool. - BikeGremlin Deathnotes – My Zettelkasten System

My interpretation and implementation of this system.

Last updated:

Originally published: